Cells, tissues and signalling molecules that surround a brain tumour are collectively known as a tumour microenvironment. They play a vital role in the tumour’s growth and survival.

In the largest study of the paediatric low grade glioma tumour microenvironment to date, researchers mapped this area and found some immune cells that may prevent the tumour from being attacked by the immune system. This could help explain why some low grade brain tumours come back after treatment.

The study involved researchers from the Everest Centre – a collaborative research centre we fund, which brings together world-leading experts from Germany and the UK. The centre is improving understanding and treatment of low grade brain tumours in children.

Together with researchers in Canada, the team published their findings in Nature Immunology.

Understanding low grade gliomas

Low grade gliomas are the most common childhood primary brain tumour. Survival rates are generally high. But these tumours can cause severe long-term health problems, and they often come back after treatment.

Previous research has shown that almost all paediatric low grade gliomas are driven by significant changes within the MAPK (mitogen activated protein kinase) pathway. This has therefore become a key target for new therapies.

Last year, dabrafenib and trametinib were approved to treat gliomas with a specific mutation that affects the MAPK pathway. Researchers are also now developing and trialling other therapies that target similar genetic changes.

A novel approach

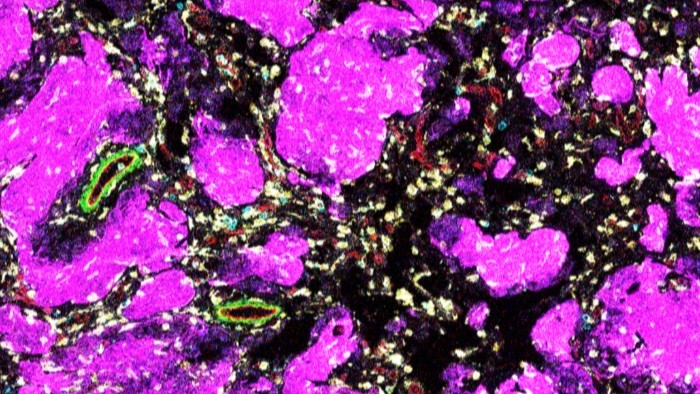

In this study, researchers used an innovative technology called imaging mass cytometry to analyse 120 tumour samples. This approach enabled new insights into the arrangement of cells and how they interact.

The study also considered differences based on age, molecular features and the tumour’s location in the brain.

What did the research find?

Myeloid cells – a type of white blood cell – were the most common immune cell in the tumour microenvironment. There were particularly high numbers of these cells in optic nerve gliomas, which are known to be associated with worse outcomes.

Their analysis suggests that a specific type of myeloid cell – those that express a protein called TIM-3 – show signals that can help the tumour avoid immune attack. Based on this new knowledge, researchers suggest that future treatments might work better by blocking both TIM-3 and MAPK activation.

Strikingly, there were low numbers of T cells. These are an important part of the immune system that usually help fight disease.

The researchers also identified an immune pattern that can indicate which tumours are likely to grow again. Once validated, this could be a useful marker for identifying patients at high risk of recurrence.

This study gives scientists the most detailed picture of the immune environment inside paediatric low grade gliomas so far. It changes how scientists think about these brain tumours – not just as a problem of tumour cells, but as a disease shaped by the tumour’s immune environment.

Romain Sigaud, group leader at Jena University Hospital and first author of the study

In the long term, this could lead to more targeted, less harmful therapies for children with these tumours and possibly for others with similar brain cancers.”

Making world-leading research possible

The Everest Centre for Research into Paediatric Low-Grade Gliomas was established in 2017 with an initial £5 million investment from The Brain Tumour Charity and its supporters. In 2022, we awarded a further £5 million to support the centre for a further five years.

This funding is possible thanks to the generosity and efforts of all those involved in the unique Everest in the Alps challenge. It brings groups of people together to climb the equivalent height of Everest (8848m) on skis in the Alps. The physically demanding endurance challenge is returning in February. Find out more